Although glass as a workable material has been traced to Sumerian sites in Mesopotamia which date from the 23rd century BC, and despite the great skill in glassmaking techniques practised by the Egyptians and Syrians, the technique of blowing glass into light and strong vessels was not invented until the middle of the 1st century BC, probably in the region of Syria. The westward migration of glassmakers from eastern Mediterranean lands ensured the rapid spread of glassblowing across the Roman Empire: through Italy, Switzerland, Germany (notably along the river Rhine, centred around Cologne), France and the Iberian peninsula. Although glassblowing sites have been found in England, many Roman vessels discovered here are likely to have been imported from Europe.

Until the introduction of glassblowing, glassmakers employed techniques such as core-forming, sagging (see Mosaic Glass), casting and grinding to produce their vessels. The invention of blowing greatly speeded the production of glass vessels, facilitating its manufacture in large quantities, in direct competition with pottery. Despite the inevitable loss of much early glass, more than enough examples have survived (often in the form of grave goods) to enable a clear picture of the diversity of shape, colour and decoration of vessels (as well as changes in tastes and styles) from the first five centuries of the craft to be recreated.

Roman glass is a soda-lime type; its main ingredient, silica being fluxed by sodium and calcium oxides, together with potassium, magnesium and aluminium oxides. The characteristic pale blue green colour of much Roman glass is the result of an impurity in the sand, namely iron oxide. Other oxides were deliberately added, giving a variety of colours: antimony for an opaque white; antimony, together with lead for an opaque yellow; cobalt for a deep blue; copper for greenish blues and opaque reds (haematinum: see our Newsletters); and manganese for pinks and purples. Manganese, in conjunction with iron oxide gave yellows and browns, but was also used as a decolouriser, since in small quantities it has the effect of neutralising the blue-greens of the iron oxide.

Strong colours are a feature of the earliest blown glass, and many fine pieces such as the famous Portland Vase, were made during this period. By the late 1st century AD however, as the effects of manganese were exploited, consumer tastes were beginning to change, and virtually colourless glass came to dominate the market by the 3rd century AD.

Glass cutting and engraving began to appear frequently on colourless vessels (see Engraved Glass, although blue green glass continued to be used for everyday utilitarian items. Within a relatively short space of time after the invention of blowing, Roman glassmakers had developed most of the important decorative techniques which are still used by makers today.

Our decision to reproduce Roman glass vessels as closely as possible meant that our starting point had to be the raw materials used by the early craftsmen. Our glass is a soda-lime type using these same ingredients as Roman 'recipes'.

Two characteristic features of our work are the presence of bubbles in the glass (seed), and the inclusion of haphazard striations (cord), both of which we can control to a certain extent. These factors, along with the thin walls and often surprisingly light weight help to give our glass a definite Roman "feel". Through much practical experience, and continuing experimentation, we have been able to re-discover and employ many of the techniques which ancient glassmakers would have used in making and decorating their vessels.

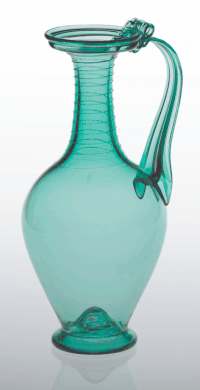

Roman artisans blew a very wide range of articles, reflecting the variety of usage: large, wide-mouthed storage jars; mould-blown square and cylindrical bottles for transportation, tall, elegant jugs and many types of bottle for use at the table, bowls for fruit, beakers for drinking, small, rounded flasks for scented oils, long-necked bottles for ointments - in fact, most items of modern day domestic glassware had their ancient counterparts. This vast range provides enormous scope for our work, and by examining original vessels, taking photographs, making drawings and thorough measurements, we are able to make faithful reproductions of many individual pieces.

When new, Roman glass had a shiny, "fire-polished" finish. The dull or iridescent surfaces that many of the surviving examples exhibit is due to the weathering processes to which they have been exposed since the Roman period. Our reproductions have the same fire-polished finish as the original glass would have had.

Most of our free-blown glass, being hand-made, has a pontil mark on the base. The vessels reflect the individual characteristics of the originals, and no two pieces are ever precisely identical in size or shape. Each piece is signed and dated by Mark.

Although most of our reproductions relate to specific items in the collections of museums around the world, some are based upon groups of similar vessels, rather than any one particular piece.

The following books contain a comprehensive summary of Roman glass forms: