Most games of chance (with the exception of wagers on physical sports) were strictly forbidden by Roman law, and were punishable with a fine fixed at four times the value of any stakes. Nevertheless, it was widely known that most caponulae and popinae (inns and eating houses) encouraged clandestine gaming in their back premises, as can be seen on wall paintings from Pompeii.

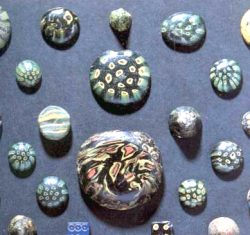

Glass Counters

These were known to Pliny the Elder as 'oculi', or eyeballs, due to their rounded appearance as a consequence of being melted.

They were made by slicing small sections of canes (c.5 - 10 mm thick), arranging them on a surface such as a terracotta tile and reheating them in a furnace until they deformed under the influence of gravity, resulting in a flattened, rounded 'button' shape.

The underside may have needed grinding to remove any particles of clay that may have stuck to it.

The 'Doctor's Grave' (left) at Colchester was discovered in 1996. Click here to see the report in The Times from September 6th.

They are a common find: for instance, the Westfälisches Römermuseum Haltern in Germany has a large selection; and the well-known Warrior's and Doctor's Graves in Colchester each has a set of monochrome counters (see photos).

The most common polychrome counters are green with small yellow circles (see photo), though many others are known.

Roman Board Games

Ludus Latrunculorum (the game of little soldiers or mercenaries), by far the most popular of all Roman board games was exempt from the law, as it was considered to be a game of skill and strategy, and could be played openly.

Martial (A.D. 40-104) records how intellectuals proudly competed in public Latrunculi championships, much like modern chess tournaments (VIII,71,7). The less privileged improvised their tabulae lusoriae (gaming boards) by scratching grids in the sand, on tiles, stone or wooden scraps, using stones, nuts, or glass calculi or gaming counters.

The Roman writer, C Calpurnius Piso, describes just such a board game:

"But if you are tired after work and yet do not want to be just lazy, but play artfully then distribute the gaming pieces cleverly on the open board and lead wars with the glass warriors so that now the white one blocks the blacks and now the black one blocks the whites.

But who didn't flee from you? Which stone retreated under your leadership? Which one has not -- death already near -- just defeated another enemy?Your battle line fights in a thousand ways: this one fleeing from an aggressor which he then nevertheless steals; this one, which was on the look-out, comes back on a long march; this one dares to enter a fight and deceives the enemy who is advancing in the hope of booty; this one is in a dangerous position and while it looks as if he is blocked, he actually blocks two enemies. This one has bigger aims: to quickly break though the rabble, advance through enemy lines and destroy the now defenceless walls?

Meanwhile, with heated fights still going on, the soldiers are scattered, but your phalanx is still complete or maybe one or two of your warriors are missing: you win and both your hands rattle with the captured group."

RULES OF PLAY:

Ludus Latrunculorum is a game for two players, each using between ten and sixteen counters.

RULES OF PLAY:

Ludus Latrunculorum is a game for two players, each using between ten and sixteen counters.

For two players, each having three (or four) counters.

The players alternate at placing a counter on any of the nine spots of the board, attempting to form a row of three of one's own counters diagonally.

The only way to do so is to occupy the central dot, therefore the player who begins will place his first counter there, but, surprisingly, he can be forced to abandon the middle spot.

Each player attempts to prevent their opponent forming a row of their own. The winner is the first to form a row of three.

A variation of the Three Men's Morris board uses a square quartered across the centre, again giving nine spots (see above). This version allows the players to use the side edges of the square to form rows of three.