ARCHIVE HOME

Welcome to the first issue of our newsletter, in which we hope to increase awareness of our work in the field of Hellenistic and early Roman non-blown glass vessels. As our work is in the context of a business, it has the advantage of being both long-term and continuous. This means that we are able to develop and refine our ideas over a long period of time, a luxury often lacking in experimental archaeology, and which can lead to insights which might not be gained in the short term.

ARCHIVE HOME

Welcome to the first issue of our newsletter, in which we hope to increase awareness of our work in the field of Hellenistic and early Roman non-blown glass vessels. As our work is in the context of a business, it has the advantage of being both long-term and continuous. This means that we are able to develop and refine our ideas over a long period of time, a luxury often lacking in experimental archaeology, and which can lead to insights which might not be gained in the short term.

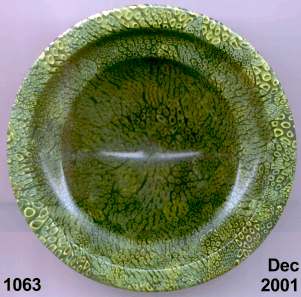

In the six months since we began to work full-time on Roman polychrome mosaic glass, we have learned a great deal regarding the techniques employed in making vessels of this type. As with all development work, progress has not been smooth, and our learning curve has had several plateaux.

When we first experimented with mosaic glass six years ago, we na´vely thought that we could fuse a disc merely by putting it into a kiln and letting the heat do all the work. Not surprisingly, this did not work. We created discs full of holes, and which stuck tenaciously to the kiln batts upon which they had been assembled!

Not until we read about Bill Gudenrath's work in Hugh Tait, ed. (1991) "5000 Years Of Glass", saw a video of his process in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and applied his techniques, did we begin to have any real success. Since the beginning of 2001 we have built on this foundation and added many improvements and refinements of our own, each of which owes its discovery to constant repetition, experimentation and learning from our mistakes. We are not stating that our techniques are exactly those used by the Roman glassmakers. We do believe, however, that we must be close, simply because we get results which compare very favourably to original mosaic glass.

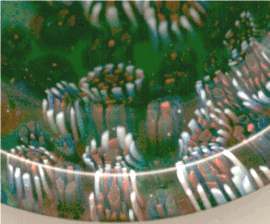

As has probably now been realised, we firmly agree with Bill concerning the techniques of mosaic glass production, and do not believe that these vessels were cast in two part moulds, as has been suggested by some authors. Our basic reasoning for this has been deduced by looking directly at the evidence on original complete vessels and fragments.

The perceived flow of glass (as shown in the pattern distortion occurring on many vessels) is not always regular, indeed, it is often multi-directional, which is not what one would expect to see in a mould-formed vessel. This suggests the use of tools whilst the glass was still hot - something that could not be attempted if it was locked in a mould.

Feet have often been added as foot-rings after the vessel was formed, indicating that the vessel was exposed and hot when it was added. It could be suggested that the vessel was cleaned and reheated after it was broken free from the mould, but this is long-winded and too involved. Our work with Roman glass over the last twelve years has led us to believe that the Roman way was often to use the simplest method available: in this case, working "live" (i.e, hand-working the hot glass), and not using a mould.

In later newsletters we intend to elaborate on our methods and arguments, since, although the same general points can be applied to many types of vessel glass from the Hellenistic period and that of the early Roman Empire, there are many details which should have their own explanations, all of which form part of the whole of the glass vessel-making techniques of that time. In fact, all of the vessel types of these periods, including ribbed bowls, mosaic glass, monochrome vessels and even cast window glass, are related in their methods of production.

We have also tackled the subject of the composition of the coloured glasses from which these vessels were made. Many of the recipes for these colours are relatively straightforward. As is widely known, the transparent glasses are easily coloured by iron, manganese, copper and cobalt oxides, but the opaque glasses are more interesting.

Many of the opaques used owe their opacity to calcium antimonate, as is also well known, and it is not difficult to reproduce opaque white, with shades of blue, green, pink and brown being readily formed, again using the metal oxides.

However, both opaque yellow (together with opaque green) and opaque red (see Newsletter 3) sit apart from the other opaque colours: yellow being coloured with lead antimonate, and red (haematinum) being coloured with copper oxide in its cuprous state. These processes are much more involved than those of other colours, and it is easy to understand why reds and yellows were generally used sparingly. These particular coloured glasses were probably expensive to buy at the time, with their preparation being a closely guarded secret.

Future newsletters will cover in greater detail many of the subjects touched on in this newsletter, and will include illustrations connected with these topics as well as pictures of our latest work.

Mark Taylor and David Hill

| vitrearii @ romanglassmakers . co . uk | 0044 (0)1264 889688 |

Unit 11, Project Workshops, Lains Farm, Quarley, Andover, Hampshire SP11 8PX, UK