Mould blown glass was extremely common throughout the Roman Empire. Glassblowing is believed to have originated in the region of Syria in the 1st century BC, and rapidly spread to Italy and the western provinces. The use of moulds helped speed up the production of many pieces, satisfying the demand for utilitarian household storage or transport vessels, as well as producing many items which may have been primarily intended as decorative.

Elaborate three, four and sometimes five-part ceramic moulds were needed to produce the highly decorated range of tableware which include 'circus beakers' and the vessels by Ennion and other named glassmakers. The moulds were probably created by impressing clay around a sculpted archetype, carefully removing the sections (adding ingenious locating lugs to ensure a snug join), and firing them. Once a mould became worn or broken, a new example could easily be made from the archetype.

These unusual and attractively decorated vessels were fairly common during the second half of the 1st century AD, and complete and fragmentary examples have been found throughout the western provinces of the Roman Empire, including Britain, France and Spain. Many have been discovered near Cologne and the Rhine valley, as well as Windisch and Brugg in Switzerland, which implies that these may represent their areas of production, although it is now thought likely that itinerant glassmakers may have purchased the fired ceramic or plaster archetypes for their mould-making from artisans not directly connected with any particular glasshouse.

These unusual and attractively decorated vessels were fairly common during the second half of the 1st century AD, and complete and fragmentary examples have been found throughout the western provinces of the Roman Empire, including Britain, France and Spain. Many have been discovered near Cologne and the Rhine valley, as well as Windisch and Brugg in Switzerland, which implies that these may represent their areas of production, although it is now thought likely that itinerant glassmakers may have purchased the fired ceramic or plaster archetypes for their mould-making from artisans not directly connected with any particular glasshouse.

Circus beakers exist in either cylindrical or ovoid forms, and their decorations conform to a variety of basic designs.

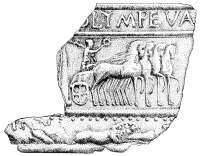

Four-horse chariots (Quadrigae) are usually depicted on cylindrical beakers with a single or double frieze. Single frieze scenes usually show four quadrigae racing in a circus, or race track (hence the name "circus beakers"), with the winner holding aloft a palm or victory wreath. The double frieze varieties also show a four-chariot race in the lower section, whilst the middle strip represents the Spina, the central barrier of the race track, which was decorated with three vast conical Metae (turning posts) at each end, lap counters in the forms of seven eggs and seven dolphins, a throne, altars, obelisks and statues. Names of the charioteers were included in a smaller third frieze immediately below the rim of the cup, the winner often having the suffix "AV" ("ave"- "hail"), or "VIC", whilst the other competitors' names end with "VA" ("vale"-"farewell", or possibly "vade"-"go"). (Gegas' name has the suffix "VA" on the lamp mentioned below).

All of the known chariot race beakers show the teams racing from left to right (anti-clockwise) around the vessels, reflecting the spectator's view of the event. Several circus beaker types also have a subordinate frieze of either a hunting scene or a decorative band of crosses, which may represent a palisade.

The most famous race track was the Circus Maximus in Rome, where, during the reign of Caligula (37-41 AD), as many as thirty-four chariot races were held daily.

The named competitors on the glass vessels were clearly celebrated figures, whose names, in various spellings, occur throughout the range of designs. The charioteer Incitatus (ICITATE - 'The Rapid One' on 047C - currently withdrawn) is mentioned by the poet Martial, and others are featured in contemporary inscriptions: Pompeius Musclosus ('The Muscular One') won 3,559 races, and Crescens was killed aged 22, having earned 1,588,346 sesterces. Gegas ('The Giant') depicted on 067A is also represented on a mid first century ceramic lamp, clad in the characteristic charioteers' segmented leather protective clothing, and holding a bridle whilst leaning casually against a winning post marker.

Gladiatorial combat scenes occur on cylindrical beakers as a single frieze, or combined with two-horse chariot (Bigae) racing scenes on some ovoid vessels. On cylindrical beakers, four pairs of gladiators armed with helmets, swords and shields (and less frequently, tridents) are shown in various stages of conflict: face-to-face combat, wounded, victorious, submitting (by raising the left hand in defeat), running away and slain. Such clashes took place in amphitheatres, and were a very popular form of entertainment. As on the chariot beakers, the gladiators' names (mostly heroic nicknames), recur on different designs, suggesting that they recall memorable combats:

Petraites ('Rocky') is named both in the Satyricon of Petronius and on an inscription at Pompeii, whilst Spiculus ('Sting' - a known favourite of Nero), Columbus ('Dove') and Proculus ('Hammer') are mentioned by the historian, Suetonius.

The fact that the same competitors' names recur on most of these vessels suggests that they were only produced for a relatively short period (Claudio-Neronian), and it is strange that later generations of gladiators and charioteers were not represented on similar glass cups, as they continued to be on mosaics, ceramics and other media. This may be due to changes in taste on the part of the buying public, but another possible explanation may be the loss of the particular skills necessary to create the archetypes and moulds for these, some of the finest and most elaborate of Roman mould blown vessels.

We use soda-lime glass of our own compositions. It is based on, and is extremely close to glass from the early Imperial Roman period. Our beakers are blown into a three-part or four-part bronze mould. The waste glass is cut off above the rim, which is then ground and polished.

When new, Roman glass had a shiny, "fire-polished" finish. The dull or iridescent surfaces that many of the surviving examples exhibit is due to the weathering processes to which they have been exposed since the Roman period. Our reproductions have the same fire-polished finish as the original glass would have had.

Since the first of our reproductions appeared several years ago, most of the currently available versions of these beakers have been completely re-sculpted, using precise measurements taken directly from casts of the originals with much greater attention to detail. This has been made possible due to the continued enthusiasm of Jennifer Price and Anna-Barbara Follmann-Schulz, as well as much helpful co-operation from other academics and museum directors.

Our reproductions fall into groups characterised by subject and vessel shape. These groups are derived from Dr. Beat Rütti's publication of the circus beakers found in Switzerland and Geneviève Sennequier's work on those found in France. The beakers are commonly blue-green in colour, but cobalt blue, emerald green and amber examples are known.