|

ARCHIVE HOME

|

The Fusing and Slumping Processes(Photographs courtesy of Hilary Cotter, Roger Dalladay and François van den Dries) |

This Newsletter covers the hot-forming processes we use to create mosaic open vessel shapes from component parts (florets from rods and canes). (See Newsletters 4 and 5 for the techniques used in making rods and canes.)

Here are some of the terms used for describing the manufacturing techniques of these vessels:

Molten glass will stick to hot metals and ceramics, so a separator has to be used. We use battwash, a suspension of refractory powders in water. Many different types of wash can be used, but we use a mixture of molochite (calcined china clay) and ball clay applied wet directly to the kiln batt. When dry, we dust the batt with dry powdered kaolin (china clay), which acts as a second protective layer. As the glass heats up to fusing temperature, it picks up a thin coating of this kaolin, which helps it to slide freely on the batt and, later, prevents it from sticking to the form. Finely-powdered clay is a likely contender as a separator for use in ancient glassmaking, although other powders such as chalk or limestone could work.

The first stage is to arrange the florets (cut at an angle - see Newsletter 4) necessary for the design on a kiln batt coated with battwash. The florets need to be packed as closely as possible, forming a disc. Assembly is relatively easy when using florets of just one pattern, but when using several different florets, deliberate and careful arrangement is important. When studying original mosaic vessels, it becomes apparent that certain combinations were favoured: in Hellenistic vessels purple, yellow and green often appear together, as do purple, blue and white. When bright red was introduced in the Imperial Roman period, it was often combined with green and white or purple and white. It is important not to create large areas of any one particular floret type or colour, which may result in an imbalance in the design.

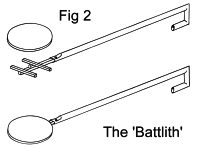

The disc is made to the same measurement as that of the form over which it will be slumped. This ensures that there will be enough glass to cover the entire form (Fig 1: Curved length AB (not the diameter).

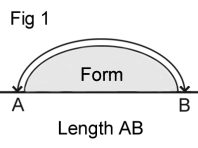

The assembled disc on its batt is pre-heated in a kiln to about 570°C. At this temperature the glass and the batt can be transferred onto the tool we use to complete the hot-forming phase: a two metre long metal pole with a support at one end for the batt. We centre the batt on a small pin which enables it to be turned whilst being worked on (Fig 2: The 'Battlith').

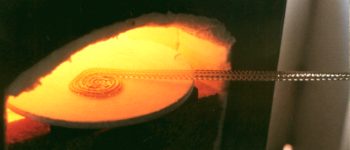

It is introduced into the glory hole for further heating. The objective is to fuse all of the florets into a single unit whilst preserving the circular shape of the disc, and not to allow the glass to adhere to the batt. This is achieved using an array of tools including various wooden sticks, a cake slice (or a fish slice) and a 10" builders' trowel. These are ideal for the job, enabling both pressing and flattening of the glass from above and separation of the glass from the batt by sliding one or more of these tools between them. The glass is kept hot enough to be worked on by sliding it in and out of the glory hole. The batt is also rotated on its pivot to allow the area needing work to benefit from the hotter areas of the glory hole, as well as to give easier access to that part of the disc.

During this fusing process the diameter will reduce, but the disc can be widened by gripping and pulling the edge with a pair of pincers whilst pinning the centre or the opposite edge with the trowel. Working evenly around the edge keeps the disc circular.

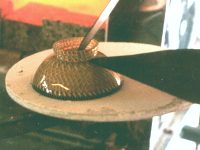

The pre-heated ceramic form is placed onto the kiln batt, and the still-hot, fused disc is placed on top. It is re-introduced into the glory hole, this time at a slightly lower temperature, and re-heated until it begins to slump under its own weight. This process is gradual, but relatively fast, and the vessel needs to be rotated to ensure even heating. Folding of the disc can pose a problem, but can be avoided by pressing the high points, encouraging the disc to slump evenly.

It is important for the rim of the vessel to touch the kiln batt, as this will ensure that the bowl will have an even lip. If this has not happened after slumping, then it is possible to encourage it to move down the side of the form to reach the kiln batt. This is done by heating the wall of the vessel until it starts to move, periodically turning the vessel to ensure an even heating and a controlled flow. Once the glass has started to run, it must not be allowed to run too far, as this results in localized thinning of the vessel wall.

When the slumping process is complete, a check has to be made to make sure that the vessel is not sticking to the form. It is then put into the hot kiln on its form and left to cool for a few minutes. When it is stiff enough, the vessel is removed from the form and left in the kiln for annealing at the end of the work period.

This is the basic procedure, and will produce a simple bowl. There are, however, other shapes and decorations which demand additional techniques:

These are added when the disc is partly fused. The network cane should be long enough to wrap around the edge of the disc, but it is easy to make up any shortfall. The cane is about 600mm long and is fed, cold, into the glory hole. When the end is hot enough to bend under its own weight, it is stuck to the end of the disc and gradually bent around it. Both the disc and the cane have to be kept hot enough to fuse, so repeated re-heats are necessary.

The cold end of the cane can be used as a handle to turn the disc on the batt. When the cane has bent around virtually all of the edge of the disc, the excess can be snapped off, using a drop of water. The two ends of the cane are then brought together and fused to the edge of the disc. Careful manipulation at this stage can produce an almost invisible join. The disc is then worked on until it is ready for slumping.

There are two forms:

Spiralled pattern:

This appears to be the earlier form of network cane pattern, and it is built up in a similar way to applying a network cane rim. One or more canes can be fed into the glory hole to be re-heated and fused into a spiral formation on a kiln batt. Often, this disc is finished with a rim cane of a different colour. It has been suggested that these types of network cane

Spiralled pattern:

This appears to be the earlier form of network cane pattern, and it is built up in a similar way to applying a network cane rim. One or more canes can be fed into the glory hole to be re-heated and fused into a spiral formation on a kiln batt. Often, this disc is finished with a rim cane of a different colour. It has been suggested that these types of network cane

bowls were built up by spiralling the cane(s) around the form. We do not agree with this, as the heat required to properly fuse the glass (particularly on the underside) is greater than that required to slump it, and if the bowl were built up in this way, the area around the shoulder in particular would tend to thin. Also, the area near the rim would tend to show a build-up and squashing of the canes. Original bowl rims show the opposite - evidence of stretching, which is the result of the vessel wall moving downwards to meet the kiln batt. Our bowls also show this effect (see our bowl nos. 1113, 1144 and 1145 in our web site archive).

bowls were built up by spiralling the cane(s) around the form. We do not agree with this, as the heat required to properly fuse the glass (particularly on the underside) is greater than that required to slump it, and if the bowl were built up in this way, the area around the shoulder in particular would tend to thin. Also, the area near the rim would tend to show a build-up and squashing of the canes. Original bowl rims show the opposite - evidence of stretching, which is the result of the vessel wall moving downwards to meet the kiln batt. Our bowls also show this effect (see our bowl nos. 1113, 1144 and 1145 in our web site archive).

Parallel row pattern:

This form has its beginnings in the Hellenistic period and lasts into the early Imperial Roman period. Network canes are cut to length and laid side by side to form a circular disc when fused. When preparing the cold disc, the 'slack' that is taken up on heating and pressing the canes together has to be taken into account. The canes need to be assembled to form an elliptical, rather than a circular disc, allowing up to 20mm 'slack'.

Parallel row pattern:

This form has its beginnings in the Hellenistic period and lasts into the early Imperial Roman period. Network canes are cut to length and laid side by side to form a circular disc when fused. When preparing the cold disc, the 'slack' that is taken up on heating and pressing the canes together has to be taken into account. The canes need to be assembled to form an elliptical, rather than a circular disc, allowing up to 20mm 'slack'.

Once again, the rim canes on both of these styles of network cane discs are added when the discs are partly fused.

These are similar to parallel row network cane discs. Rods are cut to length and laid side by side to form a circular disc when fused. The 'slack' is not as great, since fewer rods are used.

Deep, steep-sided shapes are prone to excessive folding (in the vertical plane) as the disc slumps. This makes it more difficult to form the final shape and increases the time spent on this stage.

There are several ways to overcome this:

We have used all of these methods with success.

Some of the more intricate shapes, namely 'patellae' and plates have sides with sharp changes in direction, or 'carinations'.

These can be achieved solely by grinding, but to save grinding time and to provide a guide for grinding, the glass disc can be encouraged into the sharp carinations of the form by pressing it into them with a metal tool such as a file.

The same classes of vessels that have carinations also have feet. There are two methods of making a foot:

The disc is assembled cold on a batt which has a circular groove at the centre. This groove is packed with florets which may be cut to two or three times their normal thickness of 3mm - 4mm. When heated and fused a foot-ring is formed, and the extra length of the foot-ring florets provides enough glass to completely take up the shape of the circular groove.

The top of the disc (which will later become the inside of the vessel) is dusted with a separator (powdered kaolin) and the disc is removed from the batt, turned over and balanced on the form for slumping.

Added:

Here, a separate foot-ring is formed from a length of glass rod or cane and pre-heated. It is added to the vessel body after the body has slumped, but before it is removed from the form (otherwise the body will distort during the subsequent fusing process). The foot-ring has to be carefully positioned on the base of the vessel and heated to softening temperature so that it can be pressed onto the vessel and fused to it. Any small adjustments have to be made before it is finally fused to the vessel.

Added:

Here, a separate foot-ring is formed from a length of glass rod or cane and pre-heated. It is added to the vessel body after the body has slumped, but before it is removed from the form (otherwise the body will distort during the subsequent fusing process). The foot-ring has to be carefully positioned on the base of the vessel and heated to softening temperature so that it can be pressed onto the vessel and fused to it. Any small adjustments have to be made before it is finally fused to the vessel.

In our first Newsletter we stated that we believe that mosaic glass vessels were not formed in a mould and, as shown above, the most likely explanations for their formation is a fusing and slumping process performed 'live'. This hot glass manipulation is also found in 'matt-glossy' window glass (see our article on window glass) and, very importantly, in ribbed bowl manufacture. Both monochrome and polychrome ribbed bowls are formed using these methods and the twisting patterns of many bi- and polychrome ribbed bowls is strong evidence in favour of hot glass manipulation. Our work on these vessels will be the subject of a future Newsletter.

Mark Taylor and David Hill

| vitrearii @ romanglassmakers . co . uk | 0044 (0)1264 889688 |

Unit 11, Project Workshops, Lains Farm, Quarley, Andover, Hampshire SP11 8PX, UK

Our web site is revised regularly: www.romanglassmakers.co.uk

We will be presenting a poster/display at the AIHV Congress in London in September 2003, where we will be discussing our work on ribbed bowls.